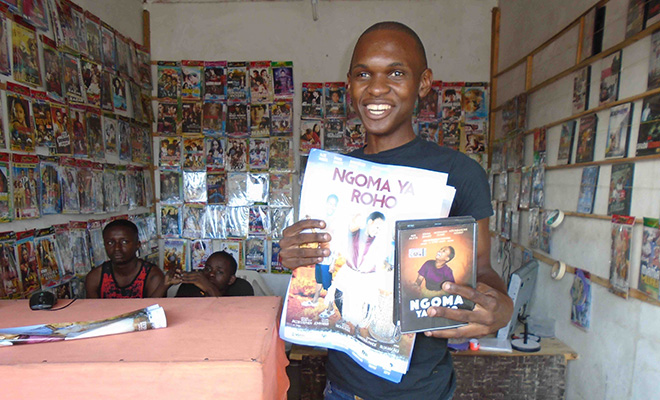

FANTA interviewed John Riber, founder and director of Media for Development International (MFDI), about the power of film to promote social and behavior change, drawing on his vast filmmaking experience, including as executive producer of the FANTA co-produced Tanzanian Swahili film Ngoma ya Roho (Dance of the Soul).

FANTA teamed with Tanzania-based MFDI and the Swahiliwood film industry to co-produce Ngoma ya Roho, a feature film that promotes positive change in social norms and behaviors known to affect nutrition. Written by an award-winning Tanzanian woman screenwriter, the film addresses the complex determinants of stunting, while educating and engaging audiences using proven “enter-educate” techniques. Ngoma ya Roho has enabled FANTA to access hard-to-reach populations across Tanzania and the wider Swahili-speaking region, with evidence-based messages on the importance of nutrition, optimal infant feeding, and dietary diversity during the critical first 1,000 days of life.

An interview with John Riber, Founder and Country Director, Media for Development International (MFDI)/Tanzania

Born and raised in India, John Riber spent the first decade of his career making films in India and Bangladesh. In 1987, Riber moved to Zimbabwe, where he and his wife Louise established a film and radio production and distribution company. They relocated Media for Development International to Tanzania in 2004 and continued to promote development and positive behavior change through socially conscious, locally produced films and media programming.

MFDI and the local film industry in Tanzania recently teamed with FANTA to produce Ngoma ya Roho (Dance of the Soul), a feature-length film about a young, pregnant woman named Minza, who learns about the importance of good nutrition during the first 1,000 days of life when her baby daughter suffers serious consequences stemming from poor nutrition and feeding practices.

FANTA staff recently sat down with Riber to ask him about his experiences with Ngoma ya Roho and the film’s potential to effect positive behavior change.

FANTA: What type of company is MFDI and what kind of work does it do?

John Riber: MFDI is a nonprofit film and radio production company that produces and distributes feature films, television series, radio dramas, and media campaign materials that address social challenges in Africa. We work mostly in Tanzania and Zimbabwe, where we’ve spent 30 years using drama formats to model behavior change.

Feature films seem like strange vehicles for delivering behavior change messages. Can films with behavior change messages really compete with films offering only entertainment?

Feature films are among the most powerful and effective tools available for the kind of work that we do in Africa. A stand-alone 90 or 120-minute feature film can cover a lot of ground in terms of effectively setting up, confronting, modeling/messaging, and resolving a story of personal and/or social behavior change.

We’ve seen tremendous success with this formula. Neria (1990), our most popular film to date, about a widow who bravely decides to fight back after her in-laws strip her of everything dear to her—even her children—following her husband’s tragic death, broke new ground by showing the potential of feature films to deliver powerful social and behavior change messages to mass audiences.

The challenge in making an effective behavior change film is finding the right balance between the education and entertainment aspects, so you don’t end up with either a popular film that doesn’t get the message right, or a film with a good message that no one wants to see. Good films start with a compelling story, usually about a sympathetic main character who’s living through a conflicted situation. Once you’ve set the scene and gotten the audience to begin empathizing with the main character’s plight, you can always find ways to inject straightforward messages.

Could you tell us a little about Ngoma ya Roho (NyR), the feature film that came out of MFDI’s collaboration with FANTA?

NyR tells a story about Minza, the young daughter of a professional dancer-father who dreams of becoming a professional dancer herself and escaping a rural life of poverty. Early in the film, Minza gets involved with her dance instructor and becomes pregnant. After her daughter is born, Minza decides to leave the baby in the village with her younger sister and mother to pursue her dreams as a dancer in the city. While Minza is away, her younger sister becomes responsible for caring for the baby, even though she has little knowledge of good nutrition and hygiene. However, things don’t work out as planned, and the rest of the film shows the drama of how Minza begins to learn about the importance of good nutrition and how poor nutrition and feeding practices can have serious consequences.

What types of behavior change messages did FANTA and MFDI embed into the film?

The key messages in NyR are about providing pregnant women and their children with proper nutrition in the first 1,000 days of life, from pregnancy through a child’s second birthday. The film includes evidence-based nutrition information and models optimal feeding and hygiene practices during the critical first 1,000 days. Throughout the story, viewers get exposed to messages about the risks of early pregnancy, good maternal nutrition, how to eat a balanced diet, breastfeeding, and good child nutrition to avoid malnutrition and stunting.

That’s important, potentially life-saving information, of course, but unless you’re a nutritionist, it may not be particularly exciting or entertaining. How did you manage to maintain viewers’ interest in the nutrition messages throughout the storyline in NyR?

The storyline of NyR reflects everyday life in Tanzania, where high rates of malnutrition affect every community as well as national development. Nevertheless, the film tries to strike a balance between providing nutrition education and behavior change messages and delivering a compelling story about one young woman’s personal experience. It’s filled with dramatic material about dancing and the world of artists, which keeps the viewers’ interest high and appeals to men as well as women. Appealing to both genders is important because success in behavior change of almost any type requires the participation of both men and women.

Could you tell us a little about how you worked with FANTA to make NyR?

MFDI has been a partner on the USAID/FANTA global award since 2012, and we began working on NyR back in 2014. FANTA staff prepared the creative brief to guide development of the film, provided nutrition expertise, and managed government collaboration on the film. MFDI, as behavior change communication and media design experts, provided creative expertise and brought in world-renowned enter-education experts and long-time collaborators to mentor the team.

We started with a NyR design workshop, and FANTA created the workshop content and brought in the content team: nutrition and local experts, including community leaders, university staff, and representatives from USAID’s implementing partners (IPs), the Tanzanian Food and Nutrition Council (TFNC), the Prime Minister’s Office, and the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MOHCDGEC). MFDI brought in the creative team, including behavior change communication experts.

The nutrition experts presented current research findings and best practices on nutrition behavior change and collectively, the group prioritized the issues for presentation in a feature film. Once fully briefed on these issues, the scriptwriters were tasked with individually developing treatments and storylines for feature films and presenting the key nutrition issues and messages in a compelling way that was relevant to the Tanzanian experience.

Finally, the vetting/review committee selected one script for production. The winning script, originally titled “MINJA,” was written by Ms. Christina Pande, an award-winning Tanzanian writer. Subsequently, MFDI selected a leading local company, JB Film Productions, to produce the film.

I understand that in Tanzania, the MOHCDGEC generally prescreens most public health films before their release to the public. How did that process work with NyR?

All film projects in Tanzania need to be approved by the Film Board before they are issued a shooting license. Finished films need censorship certification before they are released to the public. FANTA’s close relationship with the government ensured the cooperation that we needed from the authorities.

At the outset, FANTA knew that having ample government participation was important for creating a sense of ownership around the film on the part of the government, and it included TFNC in all stages of the film’s development. Not only did this open doors that may otherwise have been closed, it also helped us to get an endorsement of the film from the Hon. Ummy Mwalimu, the Minister of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children.

Getting the endorsement of a government minister on a feature film is pretty unusual. How did that happen?

Through FANTA’s nutrition connections, we organized a pre-test screening of the film for representatives from TFNC to be sure they were happy with what we had produced. When they saw the film, they liked it so much that they took it directly to the Minister and she, also, really loved it! So much so that she agreed to record her response to the film on camera, which then became an official endorsement of NyR and an extra on the DVD. In her endorsement, she urges people to watch the film and underlines the importance of dietary diversity and hygiene for young children and all Tanzanians.

How did you distribute NyR to ensure that it would be seen by a mass audience?

The FANTA project financed the production of 10,000 DVDs for distribution directly to video libraries around the country. DVD distribution is the best way to deliver the film to “hard-to-reach” audiences across rural areas of the country. Tanzania has thousands of video libraries and affordable makeshift community cinemas, called “bandas,” that provide an effective way to get films to the population via DVD distribution. A high-quality, locally produced, feature-length film like NyR, produced in Swahili using local celebrity actors, can, over time, reach huge audiences via these video libraries and informal, low-cost cinemas.

We also arranged multiple broadcasts of the film with three leading broadcasting companies, which aired the film on their most popular channels. And a growing number of Tanzanians are streaming films online on their cell phones.

Let’s talk about the numbers. What is the current viewership for NyR and how big do you expect its reach to eventually be?

I can’t tell you the precise number of viewers, but we estimate that several million viewers have already seen NyR and many more millions will see it in the years to come.

We know that Tanzanians are accessing the film in three ways: DVDs, TV, and online.

We are distributing 10,000 DVDs to video libraries in target regions around the country. Conservatively, we estimate that a DVD in a video library will, over time, reach approximately 200 viewers, which means DVD distribution of NyR will reach 2 million viewers.

NyR has been broadcast during prime time by three TV broadcasters, to date. Tanzania Broadcasting Corporation (TBC channels 1 and 2) first broadcast NyR twice on October 21–22, 2017; it later aired the film twice more on December 30–31. Azam TV, a subscription-based regional TV network with 500,000 subscribers in five Swahili-speaking countries, broadcast NyR three times between December 26, 2017 and January 1, 2018, on two of its most popular channels (Sinema Zetu and Azam Two). Clouds Plus, a subscription-based national TV network with 140,000 registered subscribers, aired NyR four times during prime viewing hours in January 2018.

Online, NyR has had over 150,000 views to date (mid-January 2018) on MFDI’s Swahiliwood YouTube channel. This was in the first two months since it was posted and without any advertising. Using YouTube analytics, we know that 75% of these views were from within Tanzania and over 90% of Tanzanian views were accessed using cell phones. We also know that 90% of the Tanzanian audience were between 18–34 years of age and 62% were female.

It’s wonderful that NyR has gotten so many views, but is just watching a film enough to get people to make positive behavior changes?

Our approach in NyR was to enter-educate—use entertainment to change health behavior. Our idea was to tell a compelling story about highly relevant nutrition issues and to make it interesting enough so that millions of people want to watch it. Ultimately, the success and effectiveness of any film, whether commercial, for behavior change communication, or both (as in the case of NyR), is determined and measured by the audience. In all cases, numbers of people reached is a determining factor. Only those who see a film can be influenced by it.

But you’re right, it is really difficult to measure the impact that one film like this has on the general population. Having said that, we should not underestimate the power of mass media to influence behaviors and change norms of the general public. Getting carefully designed films like NyR out to millions of viewers is significant.

During the film’s design, FANTA and MFDI looked for ways to increase the film’s behavior change impact by developing strategies and tools to enable local nutrition implementing partners (IPs) to use the film in their nutrition training and community nutrition outreach programs. FANTA developed a film discussion guide to help extension workers hone in on the key messages when using the film for nutrition training and education in communities across Tanzania.

What else can IPs and/or the Tanzanian Government do to amplify NyR’s behavior change impact?

NyR’s impact can be amplified in nutrition-related workshops, meetings, and conferences. With FANTA, we put together a short, 11-minute video clip focusing on the film’s main messages about good nutrition in the first 1,000 days of life. TFNC has its own training and outreach programs and they need content, especially ready-to-use content in the Swahili language. Because NyR is a high-quality production, it will have a long shelf-life. NyR will be used by government entities like TFNC and by implementing partners for nutrition training and awareness-raising for many years.

Even though the FANTA project has closed out in Tanzania, the malnutrition situation will remain a challenge for years to come, and NyR will make a lasting contribution to improving the situation if we continue to work on ensuring that the film is used as intended, by getting it out to organizations working in nutrition.

Can you share some lessons learned through making NyR that may be useful to other projects in using film for social and behavior change in Africa?

With social behavior change communication films, our sponsors and donors rightfully want and need to know how effective these interventions are in getting people to actually act upon the messages in the film in a positive way. That is the bottom line. If it doesn’t work, it should not continue to be funded.

Planning for and building in robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms into the filmmaking process at the earliest stage can help projects begin to understand the type and extent of social behavior change that comes about after people view their films. Personal and social impact can best be measured at the community level, by seeing whether and how people act upon the embedded messages.

We should build M&E activities into outreach programs to find out how IPs are using our films in their programs and how many recipients are being reached via those organizations. Investing in monitoring and evaluation follow-up in this area would help FANTA and donors to determine the level of personal community engagement with the film in a nutrition-focused setting and the level of impact the film and facilitating tools have on behavior change.

In your view, what does the future of social behavior change films look like in Tanzania and the Swahili-speaking region?

The growth potential of media industries is enormous in Africa, especially with the expansion of social media. In a region where 150–200 million people speak a common language, there is plenty of room for other Swahili-speaking countries to make films that can reach a large audience. I believe that any country in the Swahili-speaking region can do the same thing that Tanzania is doing with its film industry.

Since I’ve already asked you to get out your crystal ball, let me ask one more question about the future. What opportunities do you see to expand NyR’s reach even further in the months ahead?

There are actually several exciting possibilities on the horizon for NyR. First, Azam TV told us that they’re entering NyR in the first-ever Sinema Zetu film festival this Spring. Of course, we’re hoping it will win. But even if it doesn’t, just being nominated increases its exposure and critical acclaim immeasurably. The winning film will be announced by their jury in April 2018.

Second, we are in negotiations with TBC to arrange a special screening of the film for parliamentarians in Dodoma this year. Tanzanians take political leadership very seriously and the public is quite interested in what goes on in parliament, so we expect that such a screening would go a long way in terms of advocating for improved nutrition in the country among Tanzanian leadership. We just need to find the resources to make it happen.

We expect NyR’s reach to continue expanding via social media. The film is available on MFDI’s Swahiliwood channel, which is the 3rd largest YouTube channel in Tanzania. With 200,000 subscribers, our channel currently gets 50,000 views every day.

And finally, we need to find ways to get the film and supporting training/facilitating materials to Tanzanian (and regional) IPs working in nutrition. NyR is a wonderful tool to enhance community outreach programs that raise awareness around critical nutrition challenges in communities around the region.