Having well-trained health care providers is critical to ensuring high-quality NACS service delivery.

Ethiopia has made great strides in reducing high levels of hunger and undernutrition across the country. However, the impact of HIV and other infectious diseases on adult and child nutrition remains a concern. To address this challenge, FANTA has worked closely with the Government of Ethiopia, as well as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and implementing partners, to integrate nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS)—a client-centered approach for delivering nutrition services to people with HIV—into the country’s HIV Treatment, Care, and Support Program.

In 2014, USAID’s Food by Prescription project, the flagship nutrition and HIV project in Ethiopia, closed, and NACS funding and implementation shifted to the federal and regional governments. FANTA’s work in Ethiopia has included strengthening the capacity of six regional health bureaus (RHBs)—Oromia, Amhara, Tigray, Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, and Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region—to sustainably incorporate NACS into routine HIV services and ensure the quality of those services. Drawing on innovative approaches that leveraged existing resources, FANTA has focused on four key areas: strengthening human resource capacity, integrating NACS into routine HIV training for service providers, enhancing clinical mentorship of health staff, and improving NACS supply chain management. FANTA’s activities in Amhara, Oromia, Dire Dawa, and Addis Ababa illustrate its work in these areas.

Strengthening Human Resource Capacity in Amhara

Having well-trained health care providers is critical to ensuring high-quality NACS service delivery. To maintain quality services over time, it is essential to have the human resource capacity to provide, sustain, and expand effective NACS training, as needed. However, after taking over nutrition activities, Ethiopia’s RHBs faced considerable human resource challenges that weakened nutrition services in many facilities. Several RHBs lacked the human resource capacity to organize NACS trainings at all. Others could not provide training frequently enough to ensure that all staff were trained, which is especially important because of high turnover and frequent rotation of trained staff to other facilities. Moreover, the quality of the training often was poor due to a shortage of trainers, training materials, and job aids, as well as poor follow-up support and mentoring.

To find a cost-effective, sustainable way to address these issues, FANTA and the RHB tested a novel approach in the Amhara region in 2015: engaging local training institutions to conduct in-service NACS training. The Amhara RHB selected five institutions—Gondar University, Wollo University, Debremarkos University, Dessie Health Science College, and Debrebirhan Health Science College—to train and provide follow-up mentoring to clinical staff. Once the institutions’ roles and responsibilities were determined, FANTA trained a total of 28 people, who then became NACS master trainers. FANTA also provided materials including training manuals, monitoring and supervision checklists, mentoring checklists, training quality assessment tools, and other job aids and reference documents to the training institutions and to the RHB’s HIV and nutrition case teams.

In addition, FANTA established a pool of regional trainers to ensure that training was readily accessible and could be cascaded in the future. FANTA also developed detailed profiles that included the trainers’ contact information, educational background, years of experience, and recommendations from the RHB and other training institutions. Having the profiles made it easier for the RHB to not only find the most competent and experienced facilitators, but also to choose trainers whose education and skills were most appropriate for the staff being trained.

Resource for Future Training

To date, the five training institutions have provided seven basic and five refresher trainings. Twenty-eight health workers are cascading the integrated NACS training within their administrative zones and serving as a readily available resource for future training.

Assessments guided by a training quality checklist that FANTA developed found considerable improvement in the quality of the RHB’s NACS training. The higher-quality NACS training improved NACS service delivery in many health facilities, according to subsequent joint supportive supervision visits and standard of care assessments conducted by FANTA and the Amhara RHB. Interviews and observations conducted in selected health facilities showed that trained health workers had improved knowledge and skills in properly assessing the nutritional status of people with HIV, classifying their status, and treating clients found to be undernourished: approximately 87 percent of trained workers in the visited facilities had the required competencies to implement quality NACS services. The Amhara RHB staff also noted in the assessments that FANTA’s efforts had significantly eased the training process and helped standardize the NACS training.

“The training and subsequent mentoring from Gondar University helped us a lot in improving our knowledge and skills. Previously, I didn’t pay attention to measurements, I simply prescribed the products. But now, I acquired all the skills and started giving due attention for all elements of NACS.”

—Antiretroviral therapy (ART) worker, Gondar Hospital, Amhara

Currently, FANTA is helping the training institutions further improve their NACS training, capacity strengthening, and mentoring activities by arranging cross-learning and experience-sharing opportunities and sharing the latest reference documents. After FANTA worked with the RHB and partners to secure funding for NACS trainings, the RHB itself is now providing all necessary funds for current NACS trainings.

Integrating NACS into Routine National HIV Training in Oromia

In Ethiopia, creating a sustainable platform for providing high-quality nutrition services to clients with HIV requires that NACS be seamlessly integrated into the country’s HIV Treatment, Care, and Support program. But while nutrition services are expected to be delivered as part of routine services for people with HIV, the degree of integration varies across and within regions. Overall, weak integration and poor accountability for NACS services are partly due to the limited nutrition content in the government’s routine training for HIV service providers, called the Consolidated Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Training. In addition, the fact that nutrition services had traditionally been supported by implementing partners and not the RHBs, resulted in health facility staff bearing less accountability for nutrition services and less oversight. Furthermore, implementing partners delivered NACS training as a stand-alone, ad hoc training historically, making it more difficult for the government to integrate NACS into routine health services.

In the Oromia region, this lack of integration limited the ability of the RHB and health facilities to adequately train health workers in nutrition. After the Food by Prescription project ended in 2014, supportive supervision visits noted a significant decline in NACS service provision in some health facilities. For example, many clients with HIV were not assessed for their nutritional status, resulting in fewer clients receiving appropriate nutrition counseling and support. In addition, facilities did not consistently use proper anthropometric indices or correctly classify clients’ nutritional status.

Oromia also faced other challenges common to the RHBs: While some service providers at these facilities had received stand-alone NACS training, inconsistent provision of the training and weak supervision of NACS services led many facility staff to focus primarily on HIV services and not assume accountability for providing NACS services. In addition, because most training occurs off-site, staff had to leave their facilities, sometimes for days, to receive it. This was causing frequent interruptions in service provision and increasing the RHB’s training costs, as staff often had to attend multiple training sessions to receive all the instruction they needed to do their jobs.

Harmonizing and shortening the NACS sessions cut the 3-day NACS training to just 2 days.

FANTA and the Oromia RHB determined that to ensure both the quality of and accountability for NACS services, staff needed comprehensive training that fully integrated NACS into routine HIV training. In 2015, FANTA identified duplicate content included in both trainings and ensured that NACS content was correctly embedded within the HIV training sessions. By harmonizing and shortening the sessions, FANTA reduced the NACS curriculum by about 10 hours, taking the NACS content from 3 days to 2. FANTA piloted the shortened NACS sessions during several HIV trainings that year and found that participants still demonstrated adequate NACS knowledge and skills. Consequently, the 2-day NACS content was incorporated into the Consolidated Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Training, eliminating the need for a separate NACS training.

Using the condensed NACS training materials, FANTA also organized a combined NACS and HIV training of trainers for health workers from the Oromia RHB and for local universities, to help them cascade the training within their respective administrative zones. To standardize and improve the quality of the training, FANTA developed a package of training materials, including manuals, monitoring and supervision checklists, training quality assessment tools, and other resources, to distribute to the RHB and local universities. The RHB, in collaboration with local universities, conducted eight combined NACS and HIV trainings between 2015 and 2016, reaching 146 health care providers. Subsequent supportive supervision visits verified that NACS was successfully implemented within HIV training in the visited health facilities.

The integrated NACS and HIV training helped strengthen and sustain the integration of service delivery as well as improved the effective and efficient use of resources. Team leaders from the Oromia RHB indicated that NACS integration has saved significant amounts of funding and time. In addition, building on their collaboration with FANTA, the RHB and key partners are allocating additional resources from their own budgets to deliver integrated training, which will help support program sustainability. Furthermore, through FANTA’s efforts, a proposal has been made to integrate NACS training into Ethiopia’s HIV Treatment, Care, and Support training at the national level during the next curriculum revision.

“Since our region is very large and health facilities are … very far away from training centers, combining [NACS and HIV] trainings is beneficial. This has reduced participants’ travel costs, as some spent 2–3 days for one-way travel. Above all, the integrated training minimizes the need to leave the health facilities so frequently for various separate trainings, which caused many service interruptions. We should continue this for upcoming trainings.”

—ART team leader, Oromia RHB

Enhancing Clinical Mentorship in Nutrition in Dire Dawa

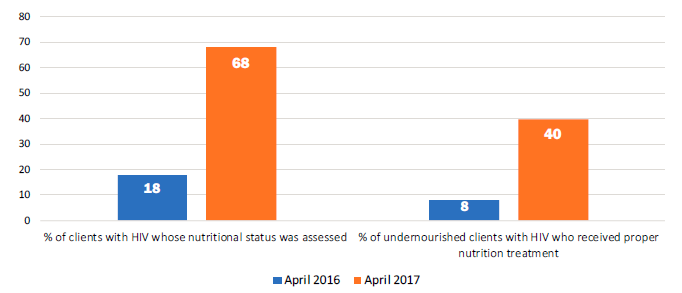

Since its implementation by the government in 2008, routine clinical mentoring for HIV services—in which mentors regularly visit health facility workers and observe them using standardized checklists—has enhanced the knowledge and skills of HIV service providers and contributed significantly to improving access to and the quality of Ethiopia’s HIV Treatment, Care, and Support Program. Despite the effort’s success, clinical mentors were still not addressing nutrition care for people with HIV adequately until recently. For example, in Dire Dawa, standard of care assessments and supportive supervision that FANTA conducted jointly with the RHB in 2016 found that only 18 percent of clients with HIV had their nutritional status assessed. Further, the nutritional status of some of these clients was misclassified and only 8 percent of undernourished clients with HIV had received nutrition treatment.

FANTA observed that NACS components were not included in the existing HIV mentoring tools, making it difficult for clinical mentors to routinely observe and provide guidance on NACS services. In collaboration with the World Food Programme (WFP) and the ICAP at Columbia University, FANTA reviewed the existing HIV mentoring tools to determine what basic NACS-specific components should be incorporated into the clinical mentoring checklist. FANTA, WFP, International Center for AIDS Care and Treatment Program, and the RHB agreed that a minimum of six NACS questions should be included in the checklist to help harmonize mentoring for both NACS and HIV services. In 2016, FANTA provided an orientation for clinical mentors from the Dire Dawa RHB and local training institutions on the NACS components. FANTA also trained the clinical mentors in charge of providing HIV mentoring programs on the basics of NACS to broaden their knowledge and skills on standard nutrition care and equip them to help service providers improve the quality of nutrition care.

Improving the Quality of NACS Services in Dire Dawa

The trained clinical mentors began providing frequent, targeted mentoring enhanced by the NACS training at the end of 2016. Since then, joint standard of care assessments of health facilities by FANTA and the RHB found that the comprehensive, harmonized clinical mentorship and use of the integrated checklist had steadily improved the quality of NACS services. As shown in the figure above, the RHB reported in April 2017, that 68 percent of clients with HIV had their nutritional status assessed, up substantially from 18 percent in April 2016. Similarly, 40 percent of undernourished clients with HIV received proper nutrition treatment in April 2017, five times more than the 8 percent a year earlier. In addition, clinical mentors now can document in their mentoring reports any NACS-related gaps or issues they observe and actions that service providers can take to address them. This provides helpful information that can further strengthen the learning environment for service providers and highlight areas where technical assistance is needed.

Improving Supply Chain Management in Addis Ababa

As part of the overall NACS package, clients who are acutely undernourished are normally provided nutrition support in the form of specialized food products. For this component of NACS to operate effectively, the NACS commodity supply chain must function efficiently and reliably. In Ethiopia, specialized food products for NACS services were historically managed through implementing partners. Over the past several years, NACS commodity management was transitioned to the government’s Pharmaceuticals Fund Supply Agency to facilitate government ownership of the NACS program and foster a more sustainable supply chain system.

Through government-led supportive supervision visits, FANTA and the RHBs assessed the supply chain management system and identified problems with the ways in which some health facilities dispensed and stored NACS commodities. The issues included dispensing commodities to ineligible clients, dispensing the wrong commodity for the nutritional diagnosis (e.g., giving food products for moderate malnutrition to clients with severe malnutrition, and vice versa), providing incorrect dosages, dispensing based on client preferences instead of the actual prescription, not providing adequate information to clients on how to use and store the commodities at home, and dispensing to clients without prescriptions. In addition, commodities were improperly stored, resulting in damage that rendered them unusable, and facilities suffered from frequent stock-outs and delayed restocking requests. The assessment also found that most pharmacists had not been trained on NACS commodity management and that pharmacy staff turnover was high. For example in Addis Ababa, FANTA found that 87 percent of pharmacy personnel had no training and the remaining 13 percent had not received training in more than 4 years.

To address the challenges, FANTA supported the development of a customized NACS commodity and supply chain management training for pharmacists in 2016. The training, which with support from the RHBs and other partners, was aligned with the Integrated Pharmaceuticals Logistics System, covered NACS commodity and stock management systems and special considerations for these commodities. The training also included a specific session on monitoring and supervising NACS commodity management.

FANTA and the Addis Ababa City Administration Health Bureau (AACAHB) organized and conducted two rounds of training on NACS commodity management for 61 pharmacy professionals in October 2016. At the end of the training, the participants and trainers discussed problems related to NACS commodity management, proposed solutions, and developed an action plan with a timeline to evaluate progress on addressing the issues. FANTA and the AACAHB supported the implementation of the action plan through joint monitoring and supportive supervision visits, along with follow-up assessments to ascertain progress. The RHB pharmacy unit also developed simple standard operating procedures on properly dispensing, storing, and using NACS commodities.

“Before the training, I didn’t know what to check on the prescriptions, but now I know which product is meant for whom with its dosage. I do verify with the prescribers if I find some mistakes or errors on the prescription paper. I record the amount of commodities dispensed daily, monitor the remaining balance, and request on time for restocking. … The training helped us in improving our pharmaceuticals supply management.”

—Pharmacy Technician, Yeka Health Center, Addis Ababa

Subsequent joint supportive supervision visits in selected health facilities in Addis Ababa found an overall improvement in commodity management after the NACS trainings, including in how accurately the commodities were dispensed. For example, the trained pharmacy personnel began verifying prescriptions for completeness and confirming that the right commodity was prescribed for the nutritional diagnosis (severe or moderate acute malnutrition). When pharmacists found incomplete or incorrect prescriptions, they cross-checked them with prescribers. The dispensers also began explaining the commodities’ proper use and storage to clients to help prevent intra-household sharing and selling. In addition, pharmacists started tracking the dispensed commodities in separate registers and compiling monthly supply records.

Facility observations also found that the storage of NACS commodities improved, as pharmacy staff started using pallets and shelves for storage, ensuring better ventilation, updating stock cards, and submitting timely requests for restocking, leading to fewer commodity stock-outs.

To help maintain these gains, the AACAHB and sub-city pharmacy personnel have started conducting regular follow-up and providing support for pharmacists at their health facilities after the training. Any emerging issues or gaps are flagged immediately and addressed in collaboration with the government supply chain unit.

Pharmacy staff play a critical role in the supply chain for NACS commodities. The commodity management improvements achieved in Addis Ababa in such a short period demonstrate how further strengthening and scale-up of integrated pharmacy training can help improve and maintain NACS service quality.

Looking Ahead: Lessons for Expanding NACS Integration in Ethiopia

As the examples from Amhara, Oromia, Dire Dawa, and Addis Ababa show, targeted innovative technical assistance can strengthen the RHBs’ capacity to implement, manage, and sustain NACS within routine HIV services. FANTA’s approaches and experiences—collaborating with RHBs and other partners to engage local training institutions to strengthen human resource capacity; incorporating NACS into existing training for service providers, clinical mentors, and pharmacy personnel; and improving NACS supply chain management—provide valuable lessons that can be leveraged in other regions. Scaling up these approaches throughout the regions can lay the foundation for long-term sustainability for NACS at the national level, and accelerate Ethiopia’s hard-earned progress against malnutrition.